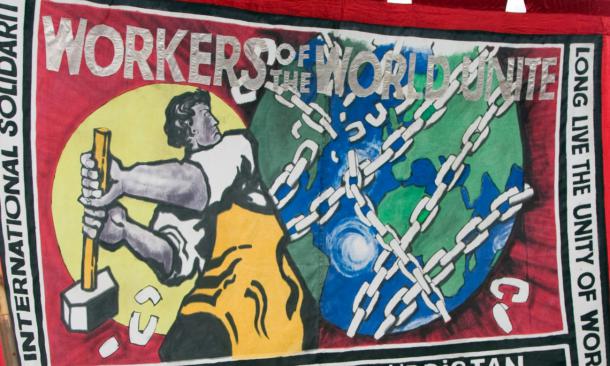

May Day: workers of the world unite and take over - their factories

Guardian 1st May 2015

The liberal UK newspaper, the Guardian - in a special article for May Day 2015 - has recognised "the fast-developing phenomenon" of fabricas recuperadas that around 15,000 workers in more than 300 workplaces have taken over following attempted closure by capital. Examples in France,Spain, Greece, Argentina and Turkey many detailed on this site are discussed. This site, along with autogestion.coop and the Marseille meeting, get a mention on the online version although not in the print.

Read the full article below:

May Day: workers of the world unite and take over – their factories

A 19th-century slogan is getting a 21st-century makeover. The workers of the world really are uniting. At least, some of them are.

The economic meltdown unleashed by the 2008 financial crisis hit southern Europe especially hard, sending manufacturing output plunging and unemployment soaring. Countless factories shut their gates. But some workers at perhaps as many as 500 sites across the continent – a majority in Spain, but also in France, Italy, Greece, and Turkey – have refused to accept the corporate kiss of death.

By negotiation, or sometimes by occupation, they have taken production into their own hands, embracing a movement that has thrived for several years in Argentina.

In France, an average of 30 mostly small companies a year, from phone repair firms to ice-cream makers, have become workers’ co-operatives since 2010. Coceta, a co-operative umbrella group in Spain, reckons that in 2013 alone some 75 Spanish companies were taken over by their former employees – roughly half the total in the whole of Europe.

A gathering in Marseille last year of representatives from worker-controlled factories drew more than 200 delegates from more than a dozen countries – including pioneers from Argentina, whose turn-of-the-century economic crash sparked a wave of fabricas recuperadas that today has left around 15,000 workers in charge at more than 300 workplaces. The fast-developing phenomenon is now a field of academic study; there are websites, such as workerscontrol.net and autogestion.coop, dedicated to it.

No two self-managed ventures launch in the same circumstances, and many face daunting obstacles: bureaucratic inertia and administrative red tape that can delay or even prevent production; legal opposition from former owners; a still-chilly economic climate; outdated machinery, or products no longer in demand. Lifelong union militants can find themselves, for the first time in their lives, making tough commercial decisions.

But many – for the time being at least – are making it work.

Contents

1.France: ‘We decided to fight’

2.Spain: ‘This was new for us’

3.Greece: ‘This is about equality’

4.Argentina: ‘At first it was rough’

5.Turkey: ‘We like coming to work now’

France: ‘We decided to fight’

Twenty minutes’ drive from the old port of Marseille, on a green and well-groomed industrial park outside the Provençal village of Gémenos, is Fralib, the largest tea factory in France.

Every year, 250-odd workers here turned six tonnes of carefully cured leaves into more than 2bn sachets of Lipton and Eléphant brand flavoured and scented teas – lemon, mint, Earl Grey – and soothing herbal infusions: linden, camomile, verbena.

But in September 2010, having spent five years steadily shifting half the factory’s production to Poland, its owner, the Anglo-Dutch consumer goods giant Unilever, summarily announced it was closing the site.

“It was … shocking,” said Olivier Lerberquier, a CGT union convenor at the factory. “Unilever France had just paid a huge dividend to shareholders. Fralib, this place, was profitable, even at half capacity. We decided to fight.”

It has been, by any standards, a long battle, but it seems nearly over: next month, 57 ex-Fralib employees, now reformed into a self-managed workers’ co-op, will switch on their machines again, and a factory silent for half a decade will once more produce tea.

Standing four-square in the cavernous main production hall at Gémenos, as long-underemployed operators checked pristine machinery and freshly trained technicians tested new quality-control equipment, Leberquier said few in France would have bet on the factory’s remaining workers getting this far.

“In the end, though, the length of the fight – 1,336 days, it was – almost helped us,” he said. “We got time to build solidarity, and a solid business plan. And even if, like our lawyer says, we’re now ‘condemned to succeed’, at least we know, for sure, that we have as good a chance as anyone.”

The workers also got money. Unilever submitted four successive redundancy plans for the 182 people still employed at Fralib in 2010. All – including one proposal to relocate to Poland on an annual salary of €6,000 – were thrown out by the employment tribunal in Marseille.

While more than half the workers, exhausted, eventually accepted a payoff, those who held out to the end were rewarded: first, the greater Marseille authority, keen to preserve jobs, agreed to buy the factory site from Unilever for €5m and pay a symbolic extra euro for the machinery. Then in June last year, the company agreed a remarkable €20m settlement to cover compensation for all unpaid wages, retraining, market research, brand promotion – and €1.5m of startup capital for the new business.

“I won’t lie – it was hard,” said Xavier Imbernou, a machine operator retraining in quality control and food safety. “We went months without pay; dug deep into our savings. Whole families suffered. But we had such support, from around the country. Our struggle became symbolic.”

Marie Sasso, who has been filling little sachets with Eléphant tea – the brand was first made near Marseille St Charles station in 1896 – since she was 17, said she never expected to find herself without a job at 55, “and never for a moment considered not fighting for it”.

She said she was “counting the days till the machines restart. All this time we’ve been maintaining them, running them once a month to see they’re working. This time, when they start, it’ll be for us. No bosses. That’s what kept us going.”

The Société Coopérative et Participative Thés et Infusions, or SCOP-TI, as the new venture is known, failed in two of its early objectives: Unilever rejected its suggestion that the factory continue to supply it with bulk tea on contract, and it refused to surrender the Eléphant brand.

“We had to rethink, radically,” said Leberquier. The co-op’s new plan has it processing 350 tonnes of tea and infusions this year and 500-600 tonnes by 2017: enough to pay its members a fair wage. It is negotiating contracts with French supermarkets to supply fairtrade teas under their own labels, but is also developing a more upmarket own-brand range. “These are premium, organic, local or regional products,” said Leberquier.

“The south of France used to produce 400 tonnes of linden a year; now it mostly comes from Latin America and the harvest here is barely 15 tonnes a year. We’ve already signed deals that will bring Provençal orchards back to life.”

The former Fralib workers’ road to self-management has involved almost everyone learning something new. “You have to realise: we did production,” said Gerard Cazorla, 57, along with Leberquier a leading light in the struggle, and recently elected president of the co-op. “Purchasing, transport, marketing, sales, distribution – all of that was Unilever’s responsibility.” Roles have been decided “democratically, and actually quite naturally”, he said, through a horizontal structure of frequent general assemblies and an elected (and instantly dismissable) 11-person managing board.

Some debates – salaries all equal or reflecting professional expertise? – have been tougher than others, Cazorla conceded. And the more militant members of the new co-operative – among them, he would be the first to admit, himself – have had to adjust to some uncomfortable realities.

There was disquiet, for example, at the necessity of working directly with France’s famously ruthless big supermarket chains, and soul-searching at the prospect of a self-employed sales team working essentially on commission. “We have to be pragmatic,” Cazorla said. “Sometimes I have to take my union cap off. We have a big factory to run and 60 salaries to pay. We’re not going to change society. There’s still going to be capitalism. But we try to do what we’re doing as best we can, and according to our values.”

Jon Henley

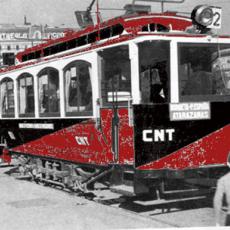

Spain: ‘This was new for us’

In a small green space tucked between tall apartment buildings, two teenage girls giggle self-consciously as they begin singing softly into their microphones. A crowd forms around them, clapping along as the videographer calls out instructions.

This hastily formed band is recording a video tribute to their city’s music school, which for five years has offered drum, piano and band lessons, among others, to around 800 students in Mataró, a small city 20 miles from Barcelona.

Most music schools wouldn’t elicit a tribute, but Mataró is different. In 2012, the school was on the brink of closure, a victim of changing political priorities and cutbacks driven by Spain’s economic crisis. As the school’s 40 teachers prepared for imminent unemployment, the students and their families took to the streets to demand that local authorities kept the school open. Finally a compromise was reached: the school would continue but its management would be privatised.

With little to lose, the school’s teachers decided to bid for the contract. “We just threw it together,” said piano teacher Aradia Sánchez de la Blanca. “The motivation was so pressing and the rage over everything we had been through was so intense that we started going down this path without thinking too much about the next steps.”

Their elation at winning the tender soon gave way to panic. “We went from basically being teachers to being members in a co-op,” said Sánchez de la Blanca. “All of a sudden we had to think about how we were going to organise ourselves, manage our finances - this was new for most of us.”

Most members had no idea what it meant to be in a co-op, said teacher Montse Anguera Gisbert. “The first year involved a lot of swearing,” she said laughing. The co-operative is now in its third year and despite the steep learning curve and the country’s economic crisis, it is growing. Today the co-op offers classes to nearly 2,000 students in seven municipalities, bringing music education to students who range from 36 months old to octogenarians.

The backbone of their growing enterprise is their monthly assemblies, where everything from management to expansion opportunities is on the table. To meet their obligation, Musicop has taken on another 40 or so part-time workers. Once there is enough fulltime work for these workers, the hope is that they can become members of the co-operative.

As Musicop’s members grapple with the challenges of self-management, they have relied extensively on the resources around them. About a year ago, Musicop set up offices in Can Fugarolas, a repurposed car dealership and repair shop that now serves as headquarters for several other co-ops dealing in everything from solar energy to consumer goods – along with other community groups.

The city of Mataró boasts a rich history of co-operatives, said Ignasi Gómez, president of Musicop. “The first co-operative launched here in the late 1800s,” he said, citing a co-op dedicated to construction launched in 1887. “Co-operatives are part of the local culture on many levels.”

Spain today is home to some 18,000 co-operatives, a vibrant movement whose international face has often been that of Mondragon, one of the world’s biggest workers’ co-operatives. Founded by local priests in the Basque country in the 1950s, Mondragon today employs nearly 75,000 people and racked up global sales of more than €11.6bn in 2013.

“Mondragon offers inspiration on what’s possible,” said Paloma Arroyo, of Coceta, a group that represents co-operatives in Spain. In 2013 alone, she said, some 75 companies across Spain were turned into co-operatives by their workers, out of 150 companies across Europe.

In a quiet primary school, pianos had been crammed into a small room where three girls were learning to play the theme song from Frozen. Elsewhere, another teacher had his hands full with eight pre-schoolerslearning the basics of rhythm in a class called Music and Movement. In an abandoned school that hosts many of Musicop’s classes in Mataró, more than a dozen pre-teens sang and waved their hands in the air as they wandered around a room singing along to Vivaldi.

For 16-year-old Aida Garcia, the classes offer a window into a world she would have never known otherwise. “I love being in these classes,” she said, adding that her dream was to play clarinet in an orchestra.

Propelled by the enthusiasm of their students, Musicop’s members have pushed forward, even though salaries dropped by 30% initially. They have begun climbing back up, and are now about 12% shy of what they were before, said Gómez. “The salaries we make are respectable, but not ideal,” he added.

Even so, few members hesitate when asked if it was worth it. “We’re better off today, because we’re empowered,” said Gómez.

Ashifa Kassam

Greece: ‘This is about equality’

Marius Kostopoulos was painstakingly dripping lemon essential oil into the 300-odd plastic bottles that he and his three colleagues had spent the past hour or so filling with all-purpose liquid household cleaner. This was not the job he was taken on to do in 2004 at Viome, a once highly profitable manufacturer of building supplies – ceramic tile adhesives and grouts, to be precise – on the industrial outskirts of Thessaloniki, Greece’s second city.

But Viome no longer really exists. Faced with the near-total collapse of the Greek construction industry, a consequent 40% slump in sales and a 30% increase in energy costs, its parent company, Philkeram-Johnson – majority owned by the local Philippou family– went spectacularly bust four years ago.

Kostopoulos and his 45 fellow production workers were already working shorter hours. In May 2011, their pay cheques stopped coming (although they have never officially been made redundant, meaning they are deprived of even minimal Greek jobless benefits). Then in September that year, Philkeram-Johnson simply abandoned the site. So Kostopoulos and 20 of his colleagues are occupying its echoing, increasingly rundown machine halls and warehousing and – for the time being, at least – making a bit of money.

“It certainly isn’t enough to survive on,” said Kostopoulos, whose wife, a daycare worker, is now at home looking after their 16-month-old son. “I need other work to get by, so I help out on evenings and weekends as a waiter at weddings, bar mitzvahs, that kind of thing. Other people’s festivities … But it’s up to half the €500 or €600 we live on each month. I couldn’t do without it.”

When Philkeram-Johnson left, the workers’ first thought was to prevent the machinery and stock being taken by the company. If that disappeared, they feared, there would be no chance of them ever seeing the €1.5m they were owed in backpay and compensation.

But what they really wanted, from the outset, was simply to keep working. “No one wants to be unemployed,” said Dimitris Koumatsioulis, 45, another ex-worker and founding co-operative member. “In Greece in particular, here and now, we couldn’t have another 45 workers unemployed, another 45 families deprived of an income.”

At the very first of their general assemblies, a proposal to stay on in the factory and run it as a self-managed co-operative won 97% approval. A delegation of workers went to Athens for talks with the employment ministry; the Philippou family, majority owners of Philkeram-Johnson, made it clear they did not envisage restarting production on the site.

By mid-2012 the Viome workers had contacted solidarity networks in Greece and abroad, exploring the possibility of producing a range of environmentally friendly soaps, washing-up liquids, softeners and detergents. The products had to be cheap to make, using existing machinery and raw materials that were simple to source.

Local citizens’ associations and unions promised to distribute a proportion of the factory’s output, followed by many of the dozens of small co-operative stores and markets then starting to spring up around Greece as the country’s formal economy spiralled downwards.

In February 2013, after a three-day solidarity event in Thessaloniki that included a benefit concert attended by more than 6,000 people, production at Viome restarted under the workers’ control, and in April last year a court recognised them as a legally constituted, not-for-profit social co-operative.

Viome products are now sold through charity and solidarity networks in Greece, Germany, the Netherlands, Switzerland and Austria. Its co-operative statutes, which emphasise the key principles of collective decision-making and ownership, refer to the venture’s “solidarity supporters”: organisations and individuals who have pledged to purchase a percentage of the factory’s output every year.

The co-operative has fought a series of court cases against Philkeram-Johnson and the Philippou family, who have repeatedly said they have no plans to use the factory themselves but now want to sell the land to pay off outstanding debts to banks, suppliers and employees.

Greece’s new radical left government is considering legislation allowing workers to legally take over factories abandoned by their owners. But ultimately, said Koumatsioulis: “We don’t want to hide it: above and beyond our own jobs and our families’ futures, this is about equality, democracy, the whole employer-employee relationship.”

If Viome eventually succeeded in its target of producing up to a tonne a day of soaps, detergents and cleaning fluids, said Kostopoulos, “we’ll be better off here – psychologically, politically, economically – than we ever were when we had bosses. We’re working for each other. That’s the difference”.

Jon Henley

Argentina: ‘At first it was rough’

All his life José Pereyra had been a waiter. For 20 years he served tables at Los Chanchitos (The Little Piggies), an old-style parrila (grill) at a strategic corner in Buenos Aires, on the borderline between two of the most densely populated middle-class neighbourhoods of the city.

Specialising in finger-licking grilled pork and generous helpings of homemade pasta, and with a faithful clientele that had kept it in business for three decades, Pereyra expected Los Chanchitos to provide firm job security.

But two years ago Pereyra realised its proprietors, who owned four other restaurants, were heading for a crash. “They owed rent on the building, they owed us back wages and had fallen behind on our social benefits payments,” said Pereyra. “I realised they were planning to close Los Chanchitos behind our backs.”

In previous decades, there would have been little Pereyra could have done to save his own job and that of his 27 other co-workers. But after Argentina’s cataclysmic economic collapse in 2001, when the country defaulted on its massive foreign debt and the government impounded all bank savings accounts, so many firms went into bankruptcy that workers were forced to find innovative solutions to save their jobs.

“Faced with the closures, instead of folding their arms and going home, many workers took the decision to form co-operatives,” said Andrés Quintana, spokesperson for CNCT, the National Confederation of Work Co-operatives.

Worker-managed firms existed before the crash. “There are probably between 5,000 and 6,000 co-operatives in Argentina today,” said Quintana. “The largest growth has been in recent years.” They provide jobs for more than 60,000 people.

For many, such as Pereyra, who worked the night shift at Los Chanchitos, forming a co-operative was a matter of survival.

“I remember the date, 23 April 2013, I spent all afternoon wandering around trying to figure out what to do,” Pereyra recalled. “The owners were pulling out and we had to take a decision. That night I called together all the waiters and the rest of the staff and proposed forming a co-operative.”

The restaurant’s employees kept the takings from that night and the next day, but when the meat and vegetable suppliers arrived, Pereyra took his first brave step. He informed the suppliers that the employees had taken over the restaurant and that daily deliveries would be paid in cash from then on.

The switch is not an easy one. “It’s a very difficult process for workers,” said Quintana. “Some are suddenly thrust from behind the counter to putting on a suit and going to work out a deal with the bank.”

“The first months were very rough, I was a traumatic wreck,” confessed Pereyra, 50. “But we had no other choice, our jobs were at stake. Many of us were over 45and would have had a hard time finding work again. For the first nine months I had to sleep at Los Chanchitos to get the business on its feet.”

On a larger scale, the workers at the large Bernardi oil storage plant in the Dock Sud area of the port of Buenos Aires were forced to take the firm over after it went bankrupt as Argentina’s economy imploded 14 years ago.

“It was a typical case of a company that collapsed during the 2001 crisis,” said José Sancha, of Decosur, the 30-member co-operative that now runs the formerly privately owned plant.

Decosur stores gas oil, petrol and fuel oil that is unloaded from tankers arriving at Buenos Aires in its 42 tanks with a combined capacity of 39,000 cubic metres.

“The first years were very tough,” Sancha recalled. “It’s an activity that requires meeting strict environmental norms, dealing with very diverse clients and securing the necessary concessions with the port authorities.”

But once the switch had been completed, business blossomed for the new cooperative. “We have now expanded to include an adjacent lot owned by another firm and we have even put in a pipe that connects us directly to the Dock Sud power plant,” said Sancha. Decosur now pipes liquid fuel to the 775-megawatt plant that feeds electric energy to a large slice of Buenos Aires.

Umbrella groups such as CNCT have stepped in to smooth the bumpy transition. “We provide training tools, we set up networks, many firms have fallen by the wayside,” said Quintana.

“The most complicated part for us was the legal settlement with the previous owners,” said Pereyra, who continues waiting at tables despite his new business role.

A pleasant surprise that followed after the co-operative took over was the return of many clients lost as the quality of the food dropped when the previous owners stopped reinvesting in the restaurant.

“If you stop paying your cook on time and you lower the quality of the meat, the client notices straight away. But when they saw that things started improving after we took over they started coming back.”

Unlike a normal business, which must turn a profit for its owner, a co-operative run by its workers tends to provide better conditions for its employees.

“We don’t retire our older employees, we find other tasks for them,” Pereyera said. “One of us needed surgery which he couldn’t afford, for example. So we got together between us and decided that the co-operative would cover the operation, because he had been working at the restaurant for 20 years. As a matter of fact, he just had the operation yesterday. A normal business maybe wouldn’t have cared, but we did.”

Uki Goni

Turkey: ‘We like coming to work now’

At a first glance, the workshop appears to be a run-of-the-mill textile factory. Long lines of knitting and weaving machines dominate the hall, while boxes filled with garments and colourful spindles of yarn are piled up in corners.

But Özgür Kazova is not like any other factory in Turkey: the four workers perched over their tables, sewing, ironing and supervising the whirring machinery, do not answer to any bosses.

Their struggle began in early 2013, when the owners of Kazova Textiles, Ümit and Mustafa Somuncu, put all 95 workers on leave after withholding their pay for several months, blaming poor business conditions. The workers were told they would receive all back-paylater, but upon their return they were informed by the company lawyer that everyone had been dismissed without compensation for “unaccounted absence from work”.

“We were dumbstruck,” said Aynur Aydemir who worked at Kazova Textiles for more than eight years. “Up until then we had been working seven days a week, up to 10 hours a day. Business seemed to be thriving. It was hard to believe that the company was really too broke to pay us.”

What was more, the owners dismantled all working machinery overnight and disappeared together with more than 100,000 finished jumpers and 40 tonnes of high-quality yarn, leaving the unpaid and now unemployed workers with knitting machines that were almost half a century old and did not work properly.

At the end of April, a handful of the former Kazova Textiles employees set up a tent in front of the old factory in order to prevent the owners taking the remaining valuables inside. Undeterred by what they said were threats and intimidation from the owners and the police, their reluctant struggle grew into a full-blown political movement.

“At first we were timid, because we had never been involved in any political movement before,” Serkan Gönüs, 42, explained. “We were scared, but little by little our confidence grew when we saw how much support we had from bystanders during those demonstrations.”

In the aftermath of Turkey’s protests in the spring of 2013, the workers decided to occupy and reopen the factory. A court ruled that the machines should go to the workers in compensation for their lost wages, and Muzaffer Yigit, 43, who has worked for Kazova Textiles since 1990, set out to repair them. Using the yarn that the old owners had left behind, the first jumpers, branded Diren Kazova (Resist Kazova), were produced. In September, the group hosted its first public fashion show.

But discord led to a split, and four workers decided to found the co-operative Free Kazova. “We found that it was not enough to just talk about workers’ rights and resistance in theory,” Gönüs said. “We wanted to come up with a sustainable model for fairer work, and be able to support ourselves.”

The Free Kazova workers have reached out to other self-managed factories and co-operatives worldwide in order to share experiences and expertise. Their aim is to produce high-quality, affordable garments for everyone interested in supporting a labour model that presents an alternative to exploitative wage work, with customers being told exactly how the money paid for each jumper is used.

“We don’t want to work for a profit, just enough for all of us to get by,” Aynur Aydemir said. “We work six hours a day, and we like coming to work in the morning now, because we are our own bosses.”

She added that Özgür Kazova jumpers were now sold not only in Turkey, but in France, Italy and Poland. “It’s actually hard to keep up with demand,” she laughed. “It proves that we are on the right track, and that many people agree with us and what we are defending.”

Constanze Letsch

Comments

Post new comment