It's possible, it's necessary - Antonio David Cattani - Redpepper

Review of 'Ours to Master and to Own' by Immanuel Ness and Dario Azzellini (eds)

In Jean-Luis Cornolli’s film Cecília (a history of Giovanni Rossi, the Italian anarchist who built, with his companions, a libertarian community in the south of Brazil at the end of the 19th century) the main character speaks sublimely of comunità anarchica sperimentale. These communist principles ensured that common property and individual autonomy were guided by economic solidarity and mutually-constructed norms of living.

After a few years, political and personal internal conflict, aggravated by material difficulties and external repression by the authorities, provoked the end of the self-managed community. One of the leaders laments the failure but Rossi calmly retorts that they had proven that it is possible to live freely without bosses and working in a spontaneous way for the common good. Despite being short-lived, the experience had various lessons for advancing the search for freedom.

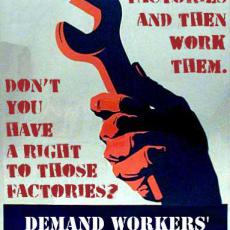

The social experiences analysed in Ours to Master and to Own illustrate this same principle: it is possible! It is possible to live without oppressive hierarchies and despotic authorities, and to live without petty competition.

Highly precarious institutional structures such as communes, workers’ councils, soviets, cooperative acts of resistance to factory/manufacturing discipline, factory occupations, self-management and so on are a dynamic proof of the role of work as an essential element in the construction of identity and social relationships. They demonstrate how cooperative workers are agents of the advancement of freedom. Their collective action attends to the interests of the whole of humanity, more so than initiatives by other agents.

The examples analysed here are varied, ranging from the classic European cases, the evolution of workers’ direct action in the United States and the experiences of the third world through to recent events in Venezuela and Brazil. This serious piece of work, put together by Immanuel Ness and Dario Azellini, deserves to be read alongside two other essential studies: Seymour Melman’s After Capitalism and Trabalhar o Mundo by Boaventura de Sousa Santos. Melman analyses the limits and possibilities of democracy in the workplace, exclusively in the US. Santos’s collection of work has a wider perspective, specifically considering cases in the global South.

Using different theoretical approaches and with distinct political orientations, these three pieces of work converge in their consideration of the inherent difficulties of libertarian action. These include internal difficulties, historical context and repressive politics, frustration and deadlock. But the authors also consider the achievements and the partial advances that have barred capitalism’s attempt to take complete control over hearts and minds.

The writers of Ours to Master and to Own point out new areas for debate, research and practical experiments, some of which are worth highlighting. These include the fact that, in general, direct action and attempts at workers’ control tend to occur as isolated experiments in just a few limited sectors of society. However, the transformation of society as a whole involves extending the democratisation of the workplace beyond isolated units.

In the wake of the bureaucratic degeneration and collapse of the Soviet system, the aim of many progressive activists today is no longer the construction of socialism, however it may be defined. Rather, it is the struggle for human rights, including the rights of ethnic and other minorities and the general expansion of the rights of citizens. Such formulations are well intentioned, but they are unable to present a comprehensive proposal for the transformation of the whole of society. In the absence of a comprehensive alternative, social movements are devoid of clear and defined objectives and an ideology that can bring together theoretical, historical and practical considerations. This condition manifests itself notably among organised structures, including left-wing parties and trade unions.

In the case of the unions, wage negotiations, working conditions and other such matters completely absorb the energy of activists. Such institutions carry out the role of modernising capitalist structures, without offering alternatives to capitalist exploitation.

Another area of debate and conflict lies in the relationship between any workplaces under worker’s control and society in general. A society that is socialised must be so in its whole, and not only in its individual units of work. But new structures have yet to be developed that can function on a society-wide level. Because of this, in the last chapter, Dario Azzellini analyses the experience of attempts at building popular communes for the modern era, such as those in the Venezuelan Bolivarian republic.

The social and environmental disaster that international capitalism has caused in the past 20 years reinforces the importance of this book. The alternative popular initiatives it describes are socially and economically far more advanced than the productivist and predatory canon of industrial capitalism. They are an antidote to the suicidal tendencies of high finance.

Workers’ control, self-management, economic solidarity and other forms of human economy are no longer merely possibilities for the achievement of utopia, but rather have become an imperative. It is necessary to put an end to the most negative trends of the dominant economics. It is necessary to overcome the mediocrity of conventional union action, and to recuperate work as an element of un-alienated human fulfilment.